I bet you think Jiminy Cricket’s heart-melting melody is pure magic. I disagree. It’s time for the cold, calculated, musical facts.

Here are some things you never realized about Jiminy Cricket’s melody:

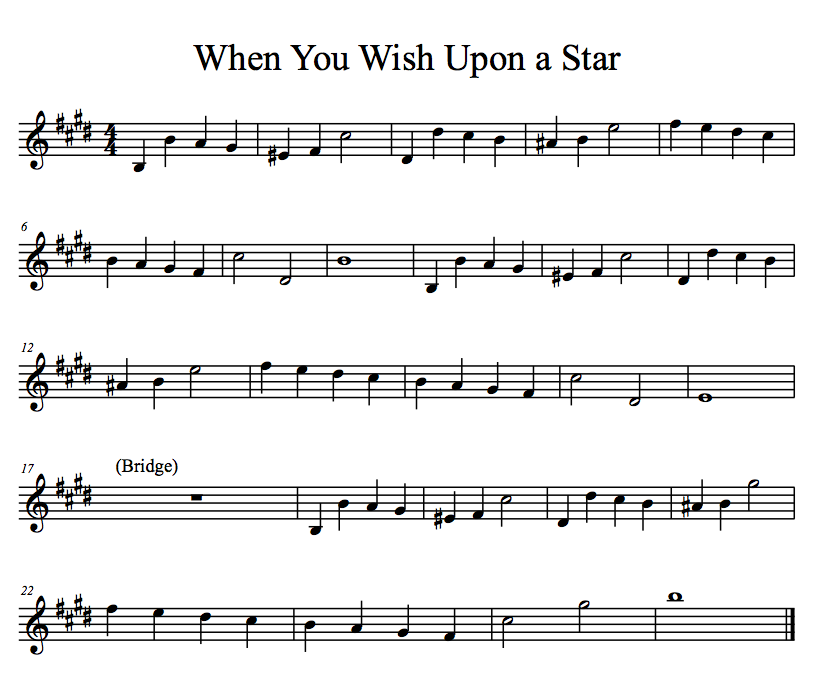

- It never repeats a single pitch consecutively. Every note immediately jumps somewhere else.

- The tonic note, which helps establish the key, DOES NOT APPEAR UNTIL 14 NOTES IN.

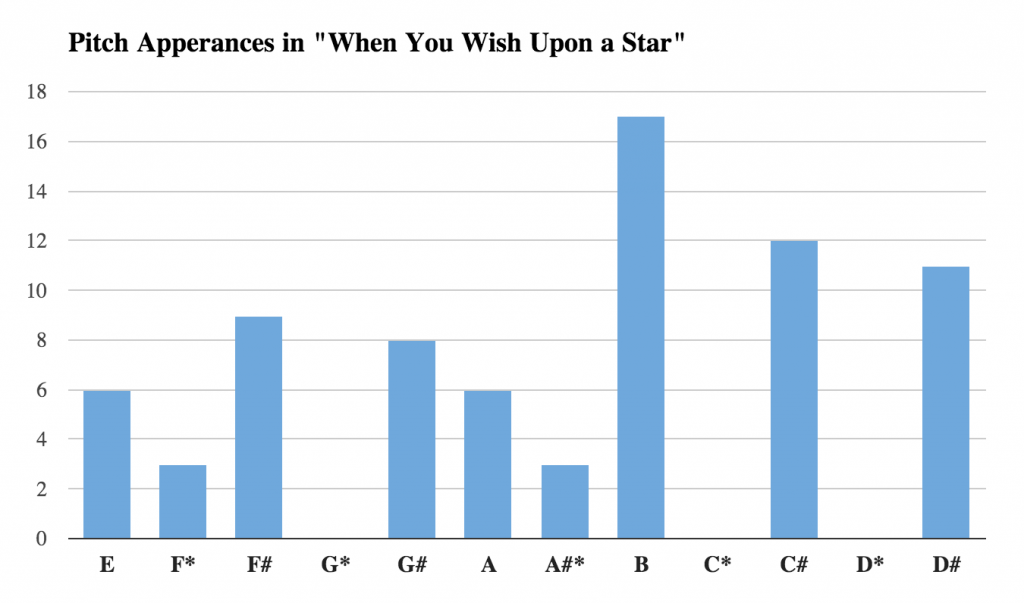

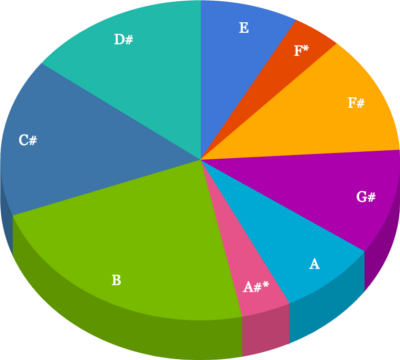

- Out of all 75 notes in the three verses, only 6 of them, or 8%, are the tonic note E.

- The melody only hits the tonic on beat one ONCE.

So what’s going on here?

Common sense would seem to say that a good melody would use notes that sound good in the key, like the tonic note. But “When You Wish Upon a Star” is all about subverting expectations. The tonic note is like the star, off in the distance. We keep longing for it, but the melody keeps skipping around it. There’s even a surprising E# on the “pon” of “upon” (I consider it E# rather than F, because it leads up to the F#).

There’s an important lesson here. You really don’t need to bash people over the head with the tonic. In fact, it’s almost always more interesting to lead a melody somewhere else. Save a tonic note for the end of a phrase, or maybe the end of an entire piece, to make it feel like we’ve made our way home.

But you know what’s even more mind blowing? Check out the 3rd verse, after the bridge part. There’s only ONE instance of the tonic note E. The end, which seems like it should resolve on the tonic, instead rises up into the night sky and ends on a very high B. I do have to admit there’s some magic beyond what can be explained by a music theory nerd.

Thanks for stopping by! If you’re a music theory nerd, you may enjoy my podcast Composer Quest.

Feel free to say hi on Twitter – @charliemccarron.

Looking at the graphs, this is a good example of why the fifth note of the scale (in this case, B) is often called the “dominant”. As Charlie notes, the tonic isn’t around a lot for this melody, but the dominant is used more prominently, even to begin and end phrases.

Something else I had noticed is that the majority of the melody stays in the upper half of the E-major scale (B, C#, and D# make up >50% of the notes used). I usually tend to view this portion of the scale as tending upwards, since it contains the “leading tone” (7th scale degree, D#). But in this case, the melody consists largely of *downward* steps.

Looking at it further, most of the motion is downward by steps, while most of what upward motion there is, is by leap. This makes those few upward leaps really standout. There’s something even more interesting if you look at where those upward leaps are going…

The first leap (“When you”) jumps to B, the next leap (“a star”) goes to C#, the third leap (“makes no”) goes to D#, and finally, the fourth leap (“you are”) jumps to the tonic, E. So the overall shape for the first half of this melody is the ascending scale that I was looking for from 5 to 1 (B-C#-D#-E)! There’s your sense of reaching for a star, but it’s cleverly hidden in descending scales.

Each verse reaches a climax (highest point) in the following note, when it moves up (scale-wise, instead of by leaping) one more note to the F#, and is resolved by a whole octave of downward scale-wise motion. Of course, as Charlie explained, the final verse actually subverts your expectations here when it actually hits the high G# instead of E, and then ends on that even higher B.